The Linux Foundation has become something of a misnomer through the years. It has extended far beyond its roots as the steward of the Linux kernel, emerging as a sprawling umbrella outfit for a thousand open source projects spanning cloud infrastructure, security, digital wallets, enterprise search, fintech, maps, and more.

Last month, the OpenInfra Foundation — best known for OpenStack — became the latest addition to its stable, further cementing the Linux Foundation’s status as a “foundation of foundations.”

The Linux Foundation emerged in 2007 from the amalgamation of two Linux-focused not-for-profits: the Open Source Development Labs (OSDL) and the Free Standards Group (FSG). With founding members such as IBM, Intel, and Oracle, the Foundation’s raison d’être was challenging the “closed” platforms of that time — which basically meant doubling down on Linux in response to Windows’ domination.

“Computing is entering a world dominated by two platforms: Linux and Windows,” the Linux Foundation’s executive director, Jim Zemlin (pictured above), said at the time. “While being managed under one roof has given Windows some consistency, Linux offers freedom of choice, customization and flexibility without forcing customers into vendor lock-in.”

A “portfolio approach”

Zemlin has led the charge at the Linux Foundation for some two decades, overseeing its transition through technological waves such as mobile, cloud, and — more recently — artificial intelligence. Its evolution from Linux-centricity to covering just about every technological nook is reflective of how technology itself doesn’t stand still — it evolves and, more importantly, it intersects.

“Technology goes up and down — we’re not using iPods or floppy disks anymore,” Zemlin explained to TechCrunch in an interview during KubeCon in London last week. “What I realized early on was that if the Linux Foundation were to become an enduring body for collective software development, we needed to be able to bet on many different forms of technology.”

This is what Zemlin refers to as a “portfolio approach,” similar to how a company diversifies so it’s not dependent on the success of a single product. Combining multiple critical projects under a single organization enables the Foundation to benefit from vertical-specific expertise in networking or automotive-grade Linux, for example, while tapping broader expertise in copyright, patents, data privacy, cybersecurity, marketing, and event organization.

Being able to pool such resources across projects is more important than ever, as businesses contend with a growing array of regulations such as the EU AI Act and Cyber Resilience Act. Rather than each individual project having to fight the good fight alone, they have the support of a corporate-like foundation backed by some of the world’s biggest companies.

“At the Linux Foundation, we have specialists who work in vertical industry efforts, but they’re not lawyers or copyright experts or patent experts. They’re also not experts in running large-scale events, or in developer training,” Zemlin said. “And so that’s why the collective investment is important. We can create technology in an agile way through technical leadership at the project level, but then across all the projects have a set of tools that create long-term sustainability for all of them collectively.”

The coming together of the Linux Foundation and OpenInfra Foundation last month underscored this very point. OpenStack, for the uninitiated, is an open source, open standards-based cloud computing platform that emerged from a joint project between Rackspace and NASA in 2010. It transitioned to an eponymous foundation in 2012, before rebranding as the OpenInfra Foundation after outgrowing its initial focus on OpenStack.

Zemlin had known Jonathan Bryce, OpenInfra Foundation CEO and one of the original OpenStack creators, for years. The two foundations had already collaborated on shared initiatives, such as the Open Infrastructure Blueprint whitepaper.

“We realized that together we could deal with some of the challenges that we’re seeing now around regulatory compliance, cybersecurity risk, legal challenges around open source — because it [open source] has become so pervasive,” Zemlin said.

For the Linux Foundation, the merger also brought an experienced technical lead into the fold, someone who had worked in industry and built a product used by some of the world’s biggest organizations.

“It is very hard to hire people to lead technical collaboration efforts, who have technical knowledge and understanding, who understand how to grow an ecosystem, who know how to run a business, and possess a level of humility that allows them to manage a super broad base of people without inserting their own ego in,” Zemlin said. “That ability to lead through influence — there’s not a lot of people who have that skill.”

This portfolio approach extends beyond individual projects and foundations, and into a growing array of stand-alone regional entities. The most recent offshoot was LF India, which launched just a few months ago, but the Linux Foundation introduced a Japanese entity some years ago, while in 2022 it launched a European branch to support a growing regulatory and digital sovereignty agenda across the bloc.

The Linux Foundation Europe, which houses a handful of projects such as The Open Wallet Foundation, allows European members to collaborate with one another in isolation, while also gaining reciprocal membership for the broader Linux Foundation global outfit.

“There are times where, in the name of digital sovereignty, people want to collaborate with other EU organizations, or a government wants to sponsor or endow a particular effort, and you need to have only EU organizations participate in that,” Zemlin said. “This [Linux Foundation Europe] allows us to thread the needle on two things — they can work locally and have digital sovereignty, but they’re not throwing out the global participation that makes open source so good.”

The open source AI factor

While AI is inarguably a major step-change both for the technology realm and society, it has also pushed the concept of “open source” into the mainstream arena in ways that traditional software hasn’t — with controversy in hot pursuit.

Meta, for instance, has positioned its Llama brand of AI models as open source, even though they decidedly are not by most estimations. This has also highlighted some of the challenges of creating a definition of open source AI that everyone is happy with, and we’re now seeing AI models with a spectrum of “openness” in terms of access to code, datasets, and commercial restrictions.

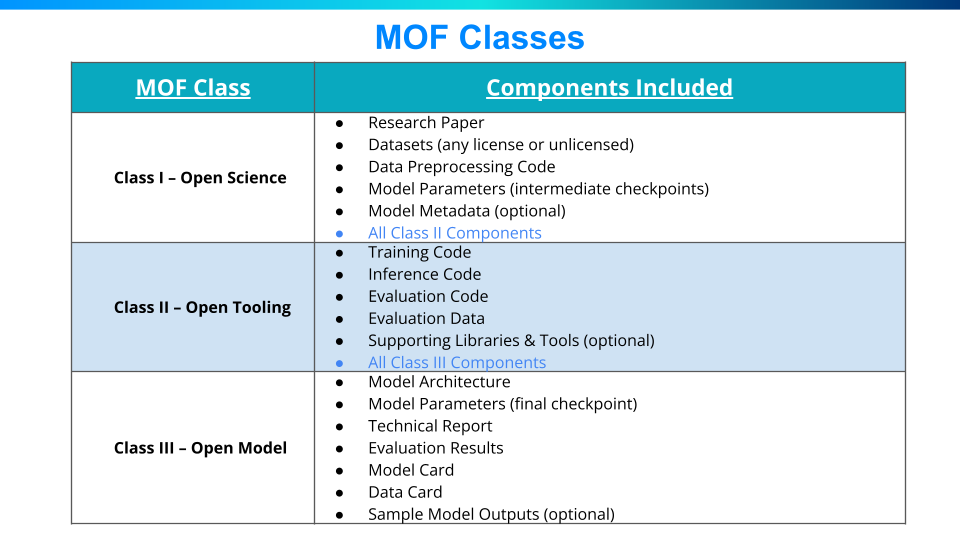

The Linux Foundation, already home to the LF AI & Data Foundation, which houses some 75 projects, last year published the Model Openness Framework (MOF), designed to bring a more nuanced approach to the definition of open source AI. The Open Source Initiative (OSI), stewards of the “open source definition,” used this framework in its own open source AI definition.

“Most models lack the necessary components for full understanding, auditing, and reproducibility, and some model producers use restrictive licenses whilst claiming that their models are ‘open source,’” the MOF paper authors wrote at the time.

And so the MOF serves a three-tiered classification system that rates models on their “completeness and openness,” with regards to code, data, model parameters, and documentation.

It’s basically a handy way to establish how “open” a model really is by assessing which components are public, and under what licenses. Just because a model isn’t strictly “open source” by one definition doesn’t mean that it isn’t open enough to help develop safety tools that reduce hallucinations, for example — and Zemlin says it’s important to address these distinctions.

“I talk to a lot of people in the AI community, and it’s a much broader set of technology practitioners [compared to traditional software engineering],” Zemlin said. “What they tell me is that they understand the importance of open source meaning ‘something’ and the importance of open source as a definition. Where they get frustrated is being a little too pedantic at every layer. What they want is predictability and transparency and understanding of what they’re actually getting and using.”

Chinese AI darling DeepSeek has also played a big part in the open source AI conversation, emerging with performant, efficient open source models that upended how the incumbent proprietary players such as OpenAI plan to release their own models in the future.

But all this, according to Zemlin, is just another “moment” for open source.

“I think it’s good that people recognize just how valuable open source is in developing any modern technology,” he said. “But open source has these moments — Linux was a moment for open source, where the open source community could produce a better operating system for cloud computing and enterprise computing and telecommunications than the biggest proprietary software company in the world. AI is having that moment right now, and DeepSeek is a big part of that.”

VC in reverse

A quick peek across the Linux Foundation’s array of projects reveals two broad categories: those it has acquired, as with the OpenInfra Foundation, and those it has created from within, as it has done with the likes of the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF).

While acquiring an existing project or foundation might be easier, starting a new project from scratch is arguably more important, as it’s striving to fulfill a need that is at least partially unmet. And this is where Zemlin says there is an “art and science” to succeeding.

“The science is that you have to create value for the developers in these communities that are creating the artifact, the open source code that everybody wants — that’s where all the value comes from,” Zemlin said. “The art is trying to figure out where there’s a new opportunity for open source to have a big impact on an industry.”

This is why Zemlin refers to what the Linux Foundation is doing as something akin to a “reverse venture capitalist” approach. A VC looks for product-market fit, and entrepreneurs they want to work with — all in the name of making money.

“Instead, we look for ‘project-market’ fit — is this technology going to have a big impact on a specific industry? Can we bring the right team of developers and leaders together to make it happen? Is that market big enough? Is the technology impactful?” Zemlin said. “But instead of making a ton of money like a VC, we give it all away.”

But however its vast array of projects came to fruition, there’s no ignoring the elephant in the room: The Linux Foundation is no longer all about Linux, and it hasn’t been for a long time. So should we ever expect a rebrand into something a little more prosaic, but encompassing — like the Open Technology Foundation?

Don’t hold your breath.

“When I wear Linux Foundation swag into a coffee shop, somebody will often say, ‘I love Linux’ or ‘I used Linux in college,’” Zemlin said. “It’s a powerful household brand, and it’s pretty hard to move away from that. Linux itself is such a positive idea, it’s so emblematic of truly impactful and successful ‘open source.’”